A San Francisco newspaper published a sympathetic feature about an illegal alien from Cambodia who had coronavirus when he was released from California’s San Quentin State Prison last July.

Chanton Bun came to the United States illegally as a child. He was convicted of armed robbery when he was 18 and served 23 years of his 49 year and eight month sentence. He left behind one child and a woman pregnant with another child.

The San Francisco Chronicle wrote a lengthy piece on Bun, painting him as someone who deserves to be protected from deportation while pointing out the flaws in the California prison system and public health policies put in place during the pandemic:

The state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation found itself unable to manage two parallel challenges: a virus that tore through its prisons, and the accelerated release of inmates to help mitigate the health crisis. Moreover, COVID left no clear path for many immigrant prisoners, whose fate is shaped by complex, conflicting policies of multiple agencies.

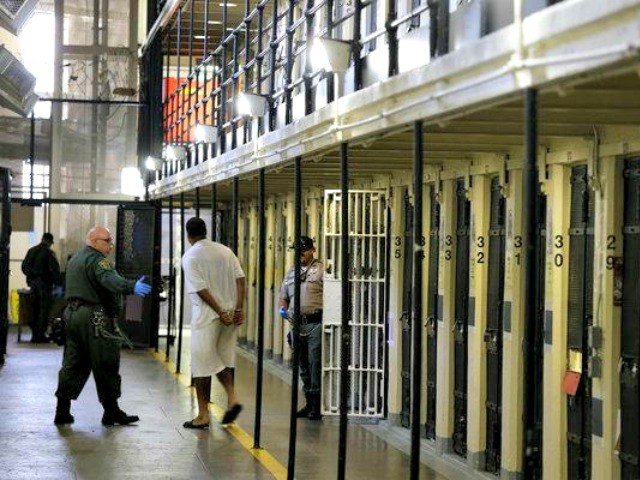

Less than a month before Bun’s release, health experts from UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco had warned prison medical officials that they needed to cut the population of San Quentin in half to avoid a devastating outbreak — one that would quickly engulf the prison’s open-tiered housing units and potentially inundate other parts of the Bay Area.In some senses, San Quentin was hamstrung. The cellblocks are poorly ventilated, and cells have bars rather than doors, which can allow pathogens to spread through the air. Once the coronavirus swept the institution, officials appeared to be flailing. They offered tests to every incarcerated person, yet testing remained voluntary under rules dictated by California Correctional Health Care Services. Last May, the state set up a program called Project Hope, which provided hotel rooms for people to quarantine after their release. That, too, was voluntary.

“As you know, we can’t hold anyone past their scheduled release date, so we cannot hold someone regardless of their COVID-19 status,” Dana Simas, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, told the Chronicle.

San Quentin had 2,258 cases during the pandemic, and 43 of those people were released after testing positive, according to the Chronicle.

But even if Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had honored the deportation detainer against Bun ,he still could have posed a public health threat. The Chronicle reported:

Had immigration officials met Bun on the day he walked out of San Quentin, they would have transported him to an immigration detention center, potentially in another state. Such facilities have been vulnerable to COVID outbreaks, owing to crowded conditions and inconsistent medical treatment. People often sit in the centers for long periods while agencies negotiate the terms of their deportation.

On a broader scale, between March and June more than 100,000 people were released from state and federal prisons. According to The Marshall Project and the Associated Press, this number represents an eight percent decrease in the national prison population since the pandemic started.

Follow Penny Starr on Twitter or send news tips to [email protected].